Problems

Donald’s sister Maggie goes to a nursery. One day the teacher at the nursery asked Maggie and the other children to stand a circle. When Maggie came home she told Donald that it was very funny that in the circle every child held hands with either two girls or two boys. Given that there were five boys standing in the circle, how many girls were standing in the circle?

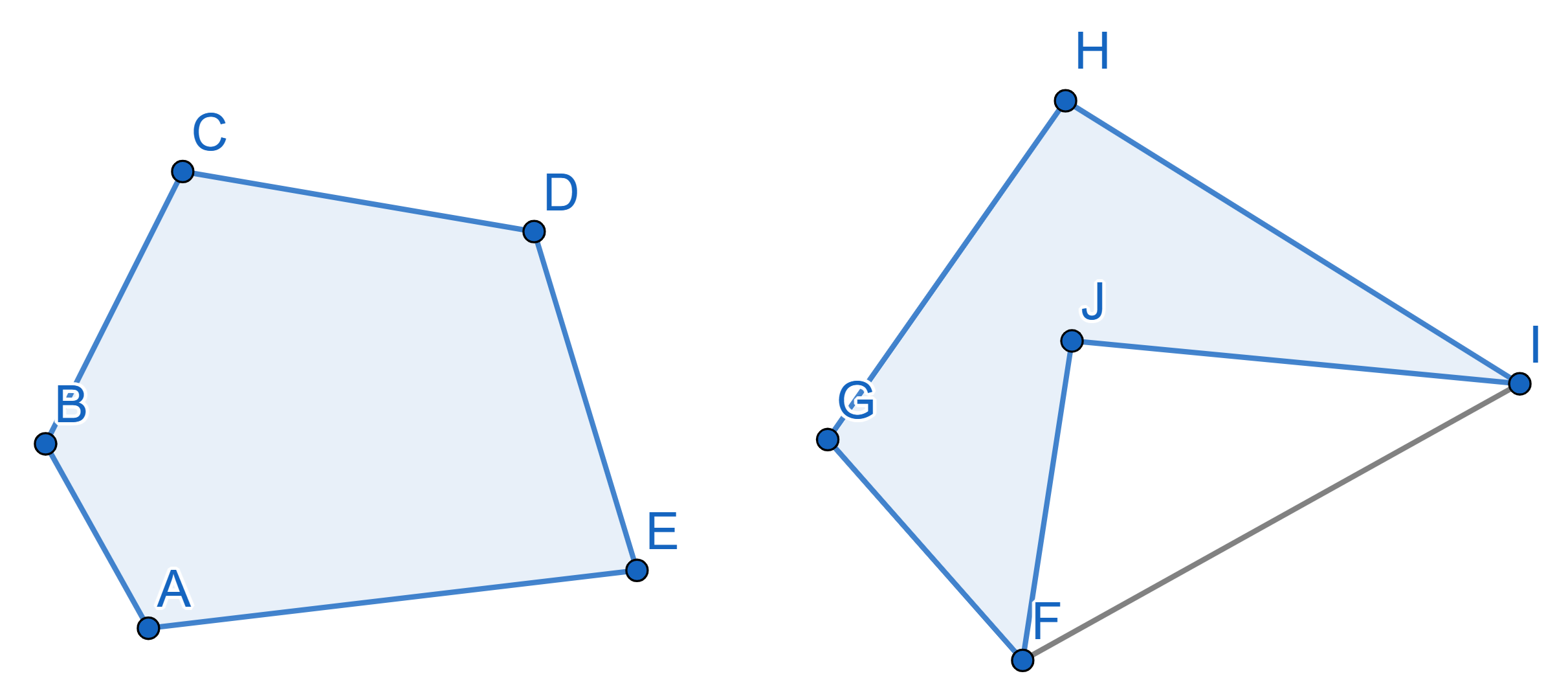

We say that a figure is convex if a segment connecting any two points

lays fully within the figure. On the picture below the pentagon on the

left is convex and the one on the right is not.

Is it possible to draw \(18\) points

inside a convex pentagon so that each of the ten triangles formed by its

sides and diagonals contains equal amount of points?

Cambria was building various cuboids from \(1\times 1\times1\) cubes. She initially built one cuboid, then increased its length and width by \(1\) and reduced its height by \(2\). She then understood that she needs the same number of \(1\times 1\times 1\) cubes to build both the original and new cuboids. Prove that the number of cubes used for each of the cuboids is divisible by \(3\).

A labyrinth was drawn on a \(5\times

5\) grid square with an outer wall and an exit one cell wide, as

well as with inner walls running along the grid lines. In the picture,

we have hidden all the inner walls from you (We give you several copies

to facilitate drawing)

Please draw how the walls were arranged. Keep in mind that the numbers

in the cells represent the smallest number of steps needed to exit the

maze, starting from that cell. A step can be taken to any adjacent cell

vertically or horizontally, but not diagonally (and only if there is no

wall between them, of course).

Is it possible to cut this figure, called "camel"

a) along the grid lines;

b) not necessarily along the grid lines;

into \(3\) parts, which you can use

to build a square?

(We give you several copies to facilitate drawing)

The triangle \(ABC\) is equilateral.

The point \(K\) is chosen on the side

\(AB\) and points \(L\) and \(M\) are on the side \(BC\) in such a way that \(L\) lies on the segment \(BM\). We have the following properties:

\(KL = KM,\) \(BL = 2,\, AK = 3.\) Find the length of

\(CM\).

Long ago in a galaxy far away there was a planet of liars and truth

tellers, it is known that liars always tell lie, and truth tellers

always respond with correct statements. All the inhabitants of the

planet look identical to each other, so there is no way to distinguish

between liars and truth tellers just by looking at them.

The planet is ruled by the government, where one may encounter honest

governors as well as liars. The government is controlled by the High

Council, where again one can meet liars and truth tellers.

Last weekend we held the verbal challenge and today we decided to demonstrate solutions of the most juicy problems.

Today we will focus on the study of Euclidean geometry of plane figures. Around 300 BCE a Greek mathematician Euclid developed a rigorous way to study plane geometry in his work Elements based on axioms (statement assumed to be correct) and theorems (statements deduced from axioms). The axioms of Euclidean Elements are the following:

For any two different points, there exists a line containing these two points, and this line is unique.

A straight line segment can be prolonged indefinitely.

A circle is defined by a point for its centre and a distance for its radius.

All right angles are equal.

For any line \(L\) and point \(P\) not on \(L\), there exists a line through \(P\) not meeting \(L\), and this line is unique.

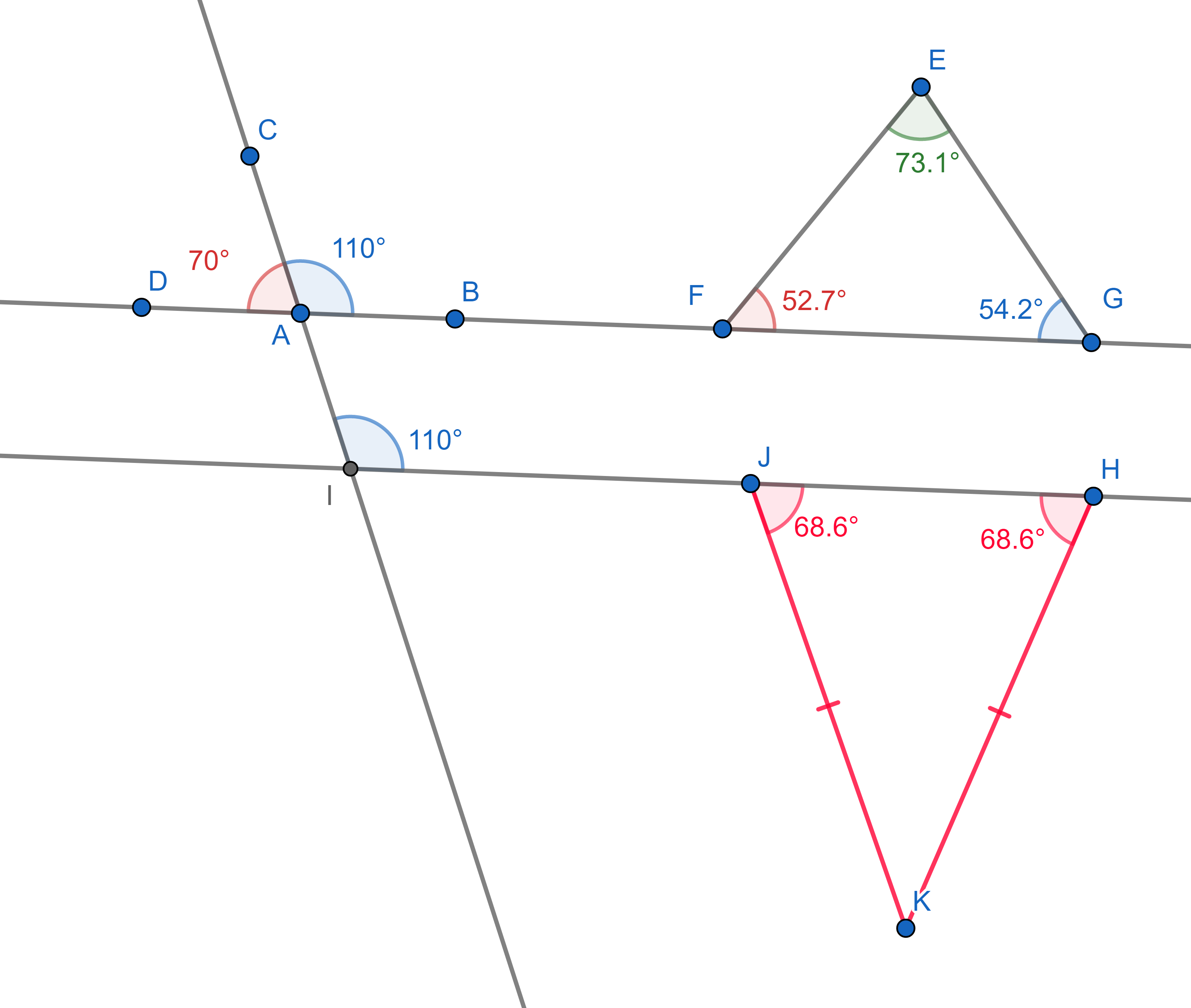

In examples we deduce from the axioms above the following basic

principles:

1. The supplementary angles (angles "hugging" a straight line) add up to

\(180^{\circ}\).

2. The sum of all internal angles of a triangle is also \(180^{\circ}\).

3. A line cutting two parallel lines cuts them at the same angles (these

are called corresponding angles).

4. In an isosceles triangle (which has two sides of equal lengths), the

two angles touching the third side are equal.

Let’s have a look at some examples of how to apply these axioms to prove geometric statements.

Consider a quadrilateral \(ABCD\). Choose a point \(E\) on side \(AB\). A line parallel to the diagonal \(AC\) is drawn through \(E\) and meets \(BC\) at \(F\). Then a line parallel to the other diagonal \(BD\) is drawn through \(F\) and meets \(CD\) at \(G\). And then a line parallel to the first diagonal \(AC\) is drawn through \(G\) and meets \(DA\) at \(H\). Prove the \(EH\) is parallel to the diagonal \(BD\).